While traditional treatments like chemotherapy and radiation have been the standard of care for many years, immunotherapy is emerging as a promising alternative for breast cancer treatment.

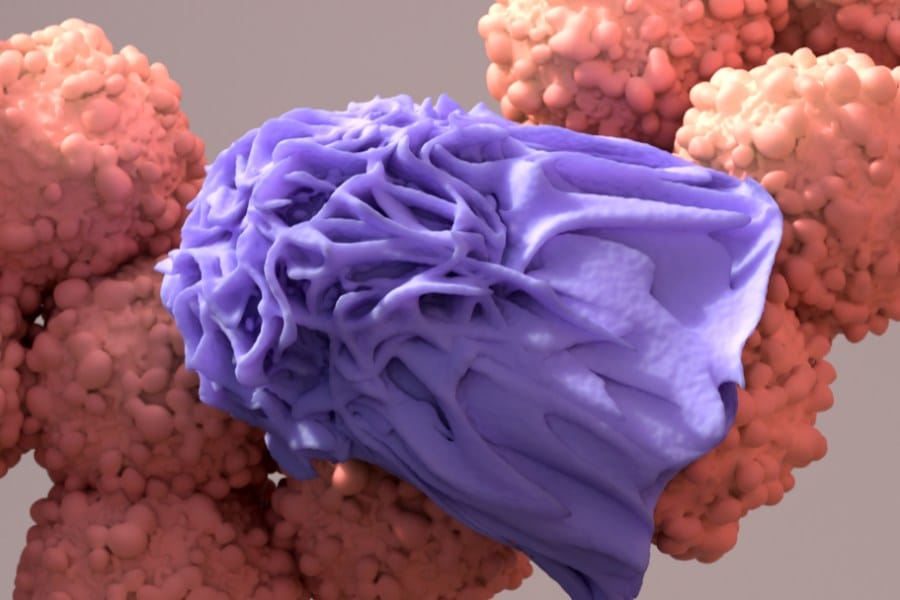

Immunotherapy works by harnessing the power of the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells more effectively.

The basics of immunotherapy involve using medications to stimulate a patient’s immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. Unlike chemotherapy, which targets rapidly dividing cells, immunotherapy targets specific proteins involved in the immune system to enhance the immune response. Clinical trials have shown that immunotherapy can be effective in treating certain types of breast cancer, including triple-negative breast cancer and HER2-positive breast cancer.

As with any cancer treatment, there are potential side effects of immunotherapy, including fatigue, nausea, and skin reactions. However, the side effects of immunotherapy are generally less severe than those associated with traditional chemotherapy. In addition, combination therapies and treatment strategies are being developed to improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy for breast cancer.

Key Takeaways

- Immunotherapy is a promising alternative to traditional breast cancer treatments like chemotherapy and radiation.

- Immunotherapy works by stimulating the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells.

- Combination therapies and treatment strategies are being developed to improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy for breast cancer.

Note: If you are someone suffering from breast cancer, there are so many resources we hope you may connect with to help support you during this fight.

Basics of Immunotherapy and Breast Cancer

IN THIS ARTICLE

Cancer develops when the body’s own cells start to grow out of control. Naturally, your immune system is programmed not to attack the body’s own cells. Genetics play a role in breast cancer, similar to conditions such as hemophilia, however – there are nuances to breast cancer. Thankfully, we have developed advanced ways to combat breast cancer.

Immunotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Unlike traditional cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which directly target cancer cells, immunotherapy helps the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.

It can be difficult for researchers to harness the power of immunotherapy for cancer treatment, but they are working on developing ways to use the body’s defense system in their favor.

Research has uncovered the different ways that the immune system is blocked from attacking cancer cells. These findings have led to a new class of drugs which are called checkpoint inhibitors. These drugs allow the immune system to recognize tumors and cancer cells as unwanted pathogens and attack them. In recent years, a dozen new cancer drugs of this class have been approved.

So far, these drugs have been drastically effective in increasing remission rates. They have been especially good at treating skin and blood cancers. But what about breast cancer, or any of the other most common cancers, like prostate or colon? Why hasn’t immunotherapy been tested as extensively or successfully for breast cancer as it has been for blood cancers?

Most forms of breast cancer are notorious for hiding from the immune system.

They are considered ‘cold‘ immunological tumors because they hide from the immune system or exclude it altogether. Researchers are figuring out new ways to label breast cancer cells as “hot” targets in order to stimulate a response from the immune system.

Mechanisms of Action

The immune system is made up of various immune cells, including T cells, which play a crucial role in recognizing and destroying cancer cells, while avoiding normal cells.

Cancer cells often evade the immune system by producing certain proteins that prevent T cells from attacking them. Immunotherapy works by blocking these proteins, allowing T cells to recognize and attack cancer cells.

There are several mechanisms of action for immunotherapy, including monoclonal antibodies, immune checkpoint inhibitors, cancer vaccines, and antibody-drug conjugates.

Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-made molecules that mimic the immune system’s ability to fight off harmful pathogens. They can be designed to recognize and bind to specific proteins on cancer cells, marking them for destruction by the immune system.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a type of immunotherapy that block proteins on immune cells that prevent them from attacking cancer cells.

By blocking these proteins, immune checkpoint inhibitors can enhance the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack cancer cells.

Cancer vaccines are another type of immunotherapy that stimulates the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. They work by introducing cancer-specific antigens into the body, which trigger an immune response against cancer cells.

Antibody-drug conjugates are a type of immunotherapy that combines monoclonal antibodies with chemotherapy drugs.

The monoclonal antibody targets specific proteins on cancer cells, while the chemotherapy drug destroys the cancer cell.

Types of Immunotherapy

There are several types of immunotherapy used to treat breast cancer, including checkpoint inhibitors, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, and cancer vaccines.

Checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and atezolizumab, are used to treat triple-negative breast cancer by blocking proteins that prevent T cells from attacking cancer cells.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are immune cells that have infiltrated a tumor. They can be extracted from the tumor, grown in the laboratory, and then infused back into the patient to enhance the immune system’s ability to recognize and attack cancer cells.

Cancer vaccines, such as the HER2 peptide vaccine and the MUC1 vaccine, are designed to stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells.

They work by introducing cancer-specific antigens into the body, which trigger an immune response against cancer cells.

Immunotherapy and Breast Cancer Types

Let’s discuss some of the more common breast cancer types in relation to immunotherapy.

HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

HER2-positive breast cancer is a type of breast cancer that tests positive for a protein called human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

This protein promotes the growth of cancer cells. Immunotherapy can be effective in treating HER2-positive breast cancer by targeting this protein.

One type of immunotherapy used for HER2-positive breast cancer is called trastuzumab, which is a monoclonal antibody that binds to HER2-positive cancer cells and blocks their growth.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Triple-negative breast cancer is a type of breast cancer that tests negative for estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and HER2.

This type of breast cancer is more aggressive and difficult to treat than other types of breast cancer. Immunotherapy has shown promise in treating triple-negative breast cancer by targeting the immune system’s response to cancer cells.

In triple-negative breast cancer, the immune system does not recognize cancer cells as foreign, allowing them to grow and spread. Immunotherapy drugs, such as checkpoint inhibitors, can help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells.

One example of a checkpoint inhibitor used for triple-negative breast cancer is pembrolizumab, which blocks a protein called PD-1 that cancer cells use to avoid detection by the immune system.

Overall, immunotherapy is a promising treatment option for some types of breast cancer, including HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer.

However, it is important to note that not all patients will respond to immunotherapy, and the best treatment approach will depend on the individual patient’s molecular subtype and other factors.

Clinical Trials and FDA Approvals

Key Immunotherapies in Trials

Immunotherapy has become a promising treatment option for breast cancer in recent years.

Clinical trials have been conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of different immunotherapies for breast cancer treatment. Pembrolizumab, Atezolizumab, Avelumab, and Durvalumab are some of the immunotherapies that have been tested in clinical trials for breast cancer.

Pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, was tested in the KEYNOTE-086 clinical trial, which included patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and PD-L1-positive tumors.

The trial showed promising results, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 21.4% and a median duration of response (DOR) of 10.3 months.

Atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, was tested in the IMpassion130 clinical trial, which included patients with metastatic TNBC. The trial showed that the combination of Atezolizumab and chemotherapy significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared to chemotherapy alone.

Avelumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, was tested in the JAVELIN trial, which included patients with metastatic breast cancer. The trial showed that Avelumab improved overall survival (OS) in patients with PD-L1-positive tumors.

Durvalumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, was tested in the MEDI3039-003 clinical trial, which included patients with advanced solid tumors, including breast cancer.

The trial showed that Durvalumab had a manageable safety profile and showed antitumor activity in patients with advanced breast cancer.

FDA-Approved Treatments

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several immunotherapies for the treatment of breast cancer. Trastuzumab, Pertuzumab, Atezolizumab, Trastuzumab emtansine, Sacituzumab govitecan, and Pembrolizumab are some of the immunotherapies that have been approved by the FDA for breast cancer treatment.

Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab are two monoclonal antibodies that target HER2-positive breast cancer. The combination of Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Atezolizumab has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of metastatic TNBC in combination with chemotherapy.

Trastuzumab emtansine, a HER2-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer.

Sacituzumab govitecan, a Trop-2-directed antibody-drug conjugate, has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of metastatic TNBC.

Pembrolizumab has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of PD-L1-positive metastatic TNBC in combination with chemotherapy.

Predictive biomarkers, such as PD-L1 expression, have been used to identify patients who are likely to respond to immunotherapy.

Clinical development of immunotherapies for breast cancer is ongoing, and further research is needed to improve the efficacy and safety of these treatments.

Combination Therapies and Treatment Strategies

Immunotherapy has shown great promise in the treatment of breast cancer, particularly in combination with other treatment modalities such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and endocrine therapy.

The following subsections will discuss some of the different combination strategies that have been explored.

Immunotherapy with Chemotherapy

Combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC).

In fact, the combination of the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab with chemotherapy is now approved by the US FDA for the first-line treatment of metastatic PD-L1+ TNBC. The combination has also demonstrated clinical activity in early-stage TNBC.

Learn more about PD-L1 Protein here.

Immunotherapy with Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies have been developed to specifically target certain proteins that are overexpressed in breast cancer cells.

Combining immunotherapy with targeted therapy has shown promise in preclinical studies.

For example, combining a PARP inhibitor with an immune checkpoint inhibitor has been shown to enhance the antitumor activity of the immune checkpoint inhibitor in preclinical models of breast cancer.

Immunotherapy with Endocrine Therapy

Endocrine therapy is often used to treat hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer.

Combining endocrine therapy with immunotherapy has been explored in preclinical studies and early-phase clinical trials.

For example, combining an aromatase inhibitor with an immune checkpoint inhibitor has been shown to be safe and well-tolerated in a phase Ib/II clinical trial.

Overall, combination therapies that include immunotherapy have shown great promise in the treatment of breast cancer.

Further research is needed to determine the most effective combinations and to identify biomarkers that can be used to predict response to treatment.

Breast Cancer Immunotherapy Study

Dr. Steven Rosenberg, chief of surgery at the National Cancer Institute, is testing immunotherapies for breast cancer treatment.

The first breast cancer participant in his study was Judy Perkins, who had Stage IV cancer that recurred and spread to her chest and liver.

She had already tried chemo and hormone treatments, and undergone a mastectomy.

In order to treat Perkins, Dr. Rosenberg did a genetic analysis of the tumor and found 62 mutations responsible for turning the cells malignant. Dr. Rosenberg went on to find immune cells that are already fighting four of those mutations.

He extracted those cells, grew them in larger quantities, and infused them back into Perkins.

After two months, the tumors in Perkins’ chest had shrunken drastically and the one in her liver had disappeared. Three years later, doctors say she is in long-lasting remission.

Perkins is one of the luckier patients. Only 14% of Rosenberg’s 42 patients have responded positively to treatment. Rosenberg hopes to improve the way researchers find mutations and immune cells for each person’s treatment. He and others hope to improve the effectiveness of breast cancer treatment and other types of solid tumors.

Doctors predict that multi-faceted approaches to cancer will be the optimal treatment plan of the future: combining immunotherapies with traditional treatments, such as chemotherapy, surgery or radiation.

Managing Side Effects and Monitoring Outcomes

Common Side Effects

Immunotherapy is a promising treatment option for breast cancer patients, but it can also cause side effects. The most common side effects of immunotherapy include fatigue, cough, diarrhea, nausea, and constipation. These side effects are usually mild to moderate in severity and can be managed with supportive care.

Patients should be monitored closely for any signs of side effects and should report any symptoms to their healthcare provider immediately. In some cases, immunotherapy may need to be temporarily or permanently discontinued if the side effects are too severe.

Measuring Clinical Outcomes

Measuring clinical outcomes is an important part of monitoring the effectiveness of immunotherapy in breast cancer patients. Overall survival is the most commonly used clinical outcome measure. This measures the length of time from the start of treatment until the patient’s death from any cause.

Other clinical outcome measures include progression-free survival, which measures the length of time from the start of treatment until the cancer starts to grow again, and response rate, which measures the percentage of patients whose cancer shrinks or disappears after treatment.

Biomarkers can also be used to monitor the effectiveness of immunotherapy in breast cancer patients. Biomarkers are substances that can be measured in the blood or other body fluids and can indicate how well the treatment is working.

For example, clinical studies have shown the presence of certain immune cells in the blood can indicate that the treatment is stimulating the immune system to attack the cancer cells.

Get Top Nursing Care During Breast Cancer Treatment

In the long term, immunotherapies appear to be a more sustainable solution than short-term treatments like chemo. ‘

The downside is that it is a time-intensive and personalized approach to care, which comes with a high price tag. It’s something that can’t be mass-produced, either.

At NurseRegistry, we match patients with breast cancer with a private nurse for care at home, where you are most comfortable.

Our nurses provide expert care following surgery administer infusions develop pain management strategies, and care for other skilled needs of individuals living with or recovering from breast cancer. Click below to discover how an in-home private nurse from NurseRegistry could benefit you or your loved one today.

Frequently Asked Questions

How successful is immunotherapy for breast cancer?

Immunotherapy has shown promising results in treating breast cancer.

However, the success rate varies depending on the subtype of breast cancer and the stage of the disease. In general, immunotherapy has been found to be more effective in treating advanced stages of breast cancer compared to early-stage breast cancer.

What are the potential benefits of immunotherapy for stage 2 breast cancer?

Immunotherapy can potentially improve the survival rates of patients with stage 2 breast cancer. It can also reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and improve the quality of life of patients.

How does immunotherapy target HER2-positive breast cancer?

Immunotherapy can target HER2-positive breast cancer by using antibodies that bind to HER2 receptors on the surface of cancer cells. This can help the immune system identify and destroy cancer cells more effectively.

In what ways is immunotherapy effective for triple-negative breast cancer patients?

Immunotherapy has shown promising results in treating triple-negative breast cancer, which is a subtype of breast cancer that is difficult to treat. It can help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells more effectively.

At what point in treatment is immunotherapy considered for breast cancer?

Immunotherapy is usually considered for breast cancer patients after other treatments, such as surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, have been tried. It is often used as a last resort for patients with advanced stages of the disease.

What are immunotherapy side effects?

Like any other cancer treatment, immunotherapy can have side effects. The most common side effects include fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and skin rash. However, the side effects of immunotherapy are generally less severe than those of chemotherapy.

Which subtype of breast cancer has the highest success rate with immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy has shown the highest success rate in treating HER2-positive breast cancer. However, it has also been found to be effective in treating other subtypes of breast cancer, such as triple-negative breast cancer.

How long is the average lifespan of a person with breast cancer?

The average lifespan of a person with breast cancer depends on various factors, such as the subtype of breast cancer, the stage of the disease, and the age of the patient. With advancements in treatment options, the survival rates of breast cancer patients have significantly improved over the years.

Is immunotherapy as hard on you as chemo?

Immunotherapy is generally less harsh on the body than chemotherapy. While chemotherapy can cause hair loss, nausea, and other severe side effects, immunotherapy has fewer side effects and is generally well-tolerated by patients. However, the effectiveness of immunotherapy varies depending on the subtype and stage of breast cancer.